Camouflage & Markings

artwork by Thierry Dekker

text by Martin Waligorski (with significant contributions by Joe Baugher)

Although the Curtiss P-36 Hawk saw very little combat in American hands, it’s role with the French Air Force was an entirely different story. Next to the Morane-Saulnier M.S.406, the Curtiss Hawk was numerically the most important fighter in French service during the war of 1939-1940.

The artwork of Thierry Dekker presented in this article was first published in Batailles Aériennes magazine no. 26

In February 1938 French government entered into negotiations with the Curtiss company for the supply of 300 fighters of the Hawk 75A type which Curtiss had offered to the Armée de l’Air. The Hawk 75A was an export version of the P-36A, and was being offered for sale with either the Pratt & Whitney Twin Wasp or the Wright Cyclone engine.

However, the unit price asked by Curtiss was considered exorbitant by the French, being almost twice as high as that of the Morane-Saulnier M.S.406. In addition, Curtiss offered a delivery schedule commencing in March 1939 at a rate of 30 planes per month which was considered totally unacceptable. Furthermore, the USAAC was itself unhappy with the Curtiss company’s inability to meet delivery schedules for its P-36As and opposed the French sale, feeling that the it would only slow things up even more.

Nevertheless, the rapidity of German rearmament made the modernization of the Armée de l’Air’s equipment a matter of the utmost urgency, so the French persisted with the negotiations. As a result of the direct intervention with President Roosevelt, a leading French test pilot Michel Detroyat was permitted to fly a Y1P-36 service test prototype at Wright Field in March 1938. He submitted a thoroughly enthusiastic report. In addition, Curtiss suggested that more acceptable delivery schedules could be offered if the French government would finance the construction and equipping of supplementary assembly facilities.

The French still felt that the unit price was too high, and on April 28, 1938 they decided to delay their decision until the completion of the test trials of the Bloch MB-150, the quoted price of which was scarcely half that of the Curtiss fighter. However, the MB-150 programme went into a series of severe and time-consuming teething troubles which eventually would delay it with almost two years. Consequently, on May 17, 1938 the French purchasing commission was instructed to order 100 Hawk airframes and 173 Pratt & Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasp engines.

Hawk 75A-1

This initial production version from the first contract was designated Hawk 75A-1 by Curtiss. According to the original plan, the majority of the Hawk 75A-1s were to be shipped by Curtiss in disassembled form to France, with assembly being completed in France by SNCAC at Bourges. The first Hawk 75A-1 was flown at Buffalo early in December 1938. The first Hawk 75A-1s were delivered by ship to France on December 14, 1938. Fourteen more Hawk 75A-1s were delivered in fully-assembled form for Armée de l’Air trials, but the rest were delivered in disassembled form. The first assembly was commenced by SNCAC in February 1939.

The Hawk 75A-1 was powered by the Pratt & Whitney R-1830-SC-G engine, offering 950 hp for takeoff. Armament comprised four 7.5 mm machine guns, two mounted in the upper decking of the fuselage nose and two in the wings. All instruments (apart from the altitude indicator) were metric calibrated. A modified seat was fitted to accommodate the French Lemercier back parachute. The throttles operated according to the French standard, i.e. in the direction reverse to the throttles of British or US aircraft. France adopted the manufacturer’s number as the official serial number, so the aircraft of this series received Nos. 01 – 100.

During March and April of 1939, the 4e and 5e Escadres de Chasse had initiated conversion from the Dewoitine 500 and 501, and by July 1, 1939 the 4e Escadre had 54 Curtiss fighters on strength and the 5e Escadre had 41. The conversion had not been without problems, one Hawk 75A-1 having crash- landed when an over-speeding propeller had caused the engine to overheat, and another one had been destroyed in a fatal crash as a result of a flat spin that developed during aerobatic trials with full fuel tanks. Throughout the entire service history of the Hawk 75A, there were problems with manoeuvrability and handling when all the fuel tanks were completely full.

Hawk 75A-2

Following the placing of the initial French order for the Hawk 75A in May of 1938, an option had been taken for 100 more machines. This option was converted into a firm order on March 8, 1939. These aircraft differed from the A-1 in having an additional 7.5 mm machine gun in each wing bringing the total firepower to six guns, some structural reinforcement of the rear fuselage, and the minor modifications necessary to permit interchange between the R-1830-SC-G and the more powerful R-1830-SC2-G, the latter affording 1050 hp for takeoff.

The new model was designated Hawk 75A-2 by Curtiss. The first A-2 was delivered to France at the end of May, 1939. The first 40 of these were basically similar to the A-1 in both powerplant and armament. The first A-2 to have both the uprated engine and the increased armament was actually the 48th off the Buffalo line. French Air Force numbering continued from the Hawk 75A-1, the first Hawk 75A-2 being numbered 101.

Hawk 75A-3

Additional 135 of the Hawk 75A-3 version were ordered by France on October 9, 1939, with improved 1200 hp R-1830-S1C3G engines and armament equal to that of the A-2. About sixty aircraft of this model reached France before the surrender, with the rest being diverted to Britain.

Hawk 75A-4

The last French order before the Armistice was for 395 Hawk 75A-4 aircraft. These were armed like the A-3s but were fitted with 1200 hp Wright R-1820-G205A Cyclone engines. Cyclone-powered 75s can be easily distinguished from Twin Wasp models by the short-chord cowling of greater diameter, the absence of engine cowling flaps and bulbous nose gun port covers.

Only two hundred and eighty-four of these A-4s were actually built, and of these, only six A-4s actually reached France before the surrender.

Colour profiles

Curtiss H-75A-3, GC II/5, Toul-Croix de Metz, May 1940

The French Hawks were in action from the first day of war in Europe. The aircraft equipped GC I/4, II/4, I/5 and II/5 and III/2, the presented example belonging to GC II/5 stationed at Toul-Croix de Metz during the time of German assault.

The aircraft carries a ”standard” fighter scheme with three-tone camouflage of Gris Bleu Foncé, Brun Foncé and Vert Foncé over Gris Bleu Clair bottom surfaces. It is difficult to be dogmatic about French camouflages of the period. Unlike the strict British or German practice of defining official patterns  applicable to specific aircraft types, the French Air Force issued only general rules referring to colours and appearance, but leaving the pattern entirely to factories, maintenance workshops and units. Consequently, some kind of uniformity is apparent with certain types (like Potez 63 series) but remains fairly random with others, like MS 406 or the aircraft in case, the H75. More often than not, a researcher has to rely on a qualified guess here and there to reconstruct a complete camouflage scheme.

applicable to specific aircraft types, the French Air Force issued only general rules referring to colours and appearance, but leaving the pattern entirely to factories, maintenance workshops and units. Consequently, some kind of uniformity is apparent with certain types (like Potez 63 series) but remains fairly random with others, like MS 406 or the aircraft in case, the H75. More often than not, a researcher has to rely on a qualified guess here and there to reconstruct a complete camouflage scheme.

This particular aircraft shows signs of combat damage – there are several repair patches on the fuselage, most possibly after bullet holes. Also, the fin is a replacement and it was most probably left in natural metal.

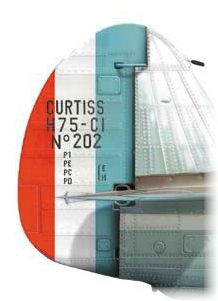

On the rudder is the typical three-line type information present on most Armée de l’Air types. This appeared in three lines on the rudder as so:

CURTISS

H75-C1

No 202

The designation C1 was not a version number, but rather referred to configuration of the aircraft. All French fighters carried the C1 suffix, the ”C” stating for Chasse (pursuit) and the 1 indicating a single-seater. However, the serial number below is most helpful for identifying the version of this particular aircraft. In this case, No. 202 reveals that this was the second production H-75A-3.

Curtiss H-75 A3, GC I/5, Suippes, May 1940

In French aviation circles there is no need to introduce Edmond Marin La Meslée, the most successful ace during the Battle of France, scoring 16 aerial victories and 4 probables. All of these victories were gained while flying a H75 with 1re Escadrille of Groupe de Chasse I/5 ”Champagne”. This Hawk 75 A3 serial no. 217 is Marin La Meslée’s personal mount.

GC I/5 operational base was Reims. During the Phoney War period, Edmond shot down but one aircraft, a Do 17 downed on 11 January 1940. However, when the German all-out attack in the West began, his score escalated very rapidly. He shot down 3 aircraft on May 11; one aircraft each on May 13, 15 and 16; three aircraft again on May 18, followed by six more until June 10. Alltogether fifteen kills within a period of four weeks, a truly remarkable achievement.

On June 11, 1940, following the combat loss of the unit’s CO, Edmond became the leader of the 1st Escadrille. His unit remained in fist line combat until June 25,  when GC 1/5 evacuated to North Africa. He survived through the Vichy period, eventually becoming a CO of CG I/5. After the fall of Axis forces in Africa, the group received P-39s and then P-47s to join the fight for France once again. On February 4, 1945, Edmond Marin La Meslée found his death on a P-47 during a ground attack mission over southern France.

when GC 1/5 evacuated to North Africa. He survived through the Vichy period, eventually becoming a CO of CG I/5. After the fall of Axis forces in Africa, the group received P-39s and then P-47s to join the fight for France once again. On February 4, 1945, Edmond Marin La Meslée found his death on a P-47 during a ground attack mission over southern France.

The famous stork emblem of the GC I/5 has its roots reaching back to SPA 3 of World War I, the prestigious l’Escadrille Guynemer.

Curtiss H-75 A3, Groupe de Chasse II/4, Xaffévillers, winter 1939/1940

GC II/4 was formed in May 1939, comprising two escadrilles: SPA 160 Diables rouges and SPA 155 Petits Poucets. Both these units had traditions reaching back to the Great War, were dismantled in 1919 and reactivated after the Munich Crisis as a result of the general re-armament programme.

At the outbreak of war in September 1939, the unit had 23 Curtiss H75 and 2 Potez 631s. It achieved combat readiness already on August 28, 1939, being deployed to field airbase at Xaffévillers (close to Rambervillers) and operating from there throughout the Phoney War period. This name, by the way, does not reflect the true character of the conflict as far as GC II/4 was concerned. On September 8, 1939, GC II/4 succeeds in destroying two Messerschmitt Bf 109Es, thereby scoring the first Allied aerial victories of World War II. The following months saw continuous and fierce aerial fighting over the Western front.

Curtiss H-75 A3, Groupe de Chasse II/4, Xaffévillers, May 1940

On May 10, 1940, the German forces attacked France and Belgium. The airfield at Xaffévillers suffered from bombardment. Two days later it was also shot up by low-flying Bf 109s. Because of this and to escape the advancing German ground forces the unit relocated to Orconte near St Dizier. There on June 3, they received a reinforcement of four Czechoslovak pilots.

But by that time the writing was already on the wall for French combatants.  On June 16, the CO of GC II/4, Cdt Borne was killed in action during a suicidal reconnaissance mission that he elected to fly himself rather than look for a volunteer among his pilots. Next day an order was received to retreat to Algeria and the unit had to burn and destroy eight of its aircraft due to the lack of pilots able to fly them. Through Poitiers and Perpignan, they reach Oran on June 21, 1940. GC II/4 was disbanded shortly thereafter.

On June 16, the CO of GC II/4, Cdt Borne was killed in action during a suicidal reconnaissance mission that he elected to fly himself rather than look for a volunteer among his pilots. Next day an order was received to retreat to Algeria and the unit had to burn and destroy eight of its aircraft due to the lack of pilots able to fly them. Through Poitiers and Perpignan, they reach Oran on June 21, 1940. GC II/4 was disbanded shortly thereafter.

During the entire campaign, the pilots of GC II/4 claimed 82 aerial victories (individual or shared) and 58 damaged enemy aircraft for the loss of 24 fighters, 9 pilots killed and 9 wounded.

The Aftermath

291 Hawk 75 fighters were actually taken on strength by the Armée de l’Air before the collapse of French resistance. The Hawk-equipped fighter units were in action from almost the first day that the war began in Europe. These units claimed a total of 230 confirmed kills and 80 probables against own losses totalling only 29 aircraft destroyed in aerial combat. Although the figures are probably over-optimistic, it seems fair to say that the French Hawks gave much better than they got.

Against its principal adversary, the Messerschmitt Bf 109 E, the Hawk suffered from a serious speed disadvantage of over 50 km/h. However, it was an excellent dogfighter, much more agile than Bf 109 and could easily outturn it in most manoeuvres. It also had a superior diving speed, which allowed a more experienced French pilot to break off the engagement at will provided that there was enough altitude.

In terms of general reliability, the Curtiss fighter was strongly built and could withstand a lot of punishment. The later Cyclone engines of A-4 models proved unreliable, but this was not the case with Twin Wasp-powered variants that took part in combat.

However, the Achilles’ heel of the H75 was the armament. Similarly to other French fighters of the period, its 7.5 mm guns were prone to freezing and malfunction at altitude. Even when working, the guns were practically ineffective at distances longer than 150m. The pilots bitterly regretted the absence of a 20 mm cannon which were available in Bloch 152s and Dewoitine 520s.

After the collapse of French resistance, a number of ordered aircraft was lost en route to French ports. As mentioned before, only six A-4s actually reached France before the Armistice. Thirty A-4s destined for France were lost at sea during transit, seventeen were disembarked in Martinique and a further six were unloaded in Guadeloupe. These machines were, incidentally, shipped from the West Indies to Morocco during 1943-44, placed in flying condition and used for training, their unreliable Cyclone 9 engines being replaced by Twin Wasps. The rest of the French Hawk 75A-4 order was taken over by Britain as Mohawk IVs.

The Armée de l’Air Hawks which had not escaped to unoccupied French territory or flown to England were taken over by the Luftwaffe. Some of the Armée de l’Air Hawk 75As were captured while still in their delivery crates. These were transported to Germany, whey they were overhauled and assembled by the Espenlaub Flugzeugbau, fitted with German instrumentation, and then sold to Finland. Finland received 36 former Armée de l’Air Hawk 75A-1s, A-2s and A-3s, along with eight former Norwegian Hawk 75A-6s. These Finnish Hawks participated in the war on the Axis side when Finland entered the war against the Soviet Union on June 25, 1941. These Hawks gave a good account of themselves in Finnish service, and some Hawks remained in service in Finland until 1948.

After the Armistice, GC I/4 and I/5 continued flying their Hawks with the Vichy Air Force, the former unit based at Dakar and the latter at Rabat. These Vichy Hawk 75As were to fight against other American planes when the Allies made the Operation Torch landings in North Africa in November 1942. In an air battle between these Hawks and carrier-based Grumman F4F Wildcats, 15 Vichy planes were shot down versus the loss of seven Wildcats. It is ironic that this accounts for about the only occasion during the Second World War in which American-built planes fought against each other.

Sources

Literature:

- Curtiss Aircraft, 1907-1947, Peter M Bowers, Naval Institute Press, 1979

- The Curtiss Hawk 75, Aircraft in Profile No. 80, Profile Publications, Ltd. 1966

- War Planes of the Second World War, Fighters, Volume Four, William Green, Doubleday, 1961.

- Air Enthusiast, Volume 1, William Green et al, Doubleday, 1971.

This article was originally published in IPMS Stockholm Magazine in November 2003.