Text by Martin Waligorski

Photos: US Naval Historical Center

The Scharnhorst and Gneisenau ships were invariably mentioned at the same time, and are fondly remembered as being ”the ugly sisters” due to the fact they prowled together, and the havoc they wrought to British shipping. Designed in mid-1930s and being the first German ships to be built outside of the limitations of the Versailles treaty, the twins were designed for a formidable maximum speed and extended range to allow for commerce raiding. Scharnhorst and Gneisenau could make 32 knots, superior to most of the ships of the Royal Navy, not to mention their own destroyer escort!

The armament was a weak point, both ships carrying 9 11″ guns, left over from cancelled pocket battleships. If a later proposal to upgrade the main armament to six 15-inch (380 mm) guns in three twin turrets had been implemented, it would make a very formidable opponent, faster than any British capital ship and nearly as well armored. But due to constraints of German pre-war economy and those imposed later by World War II, this modification was never carried out, until it was too late for it to make any difference.

War events eventually separated both ships, and each met a sad end at its own individual way – the Gneisenau scuttled in the entrance of the Gdynia harbour, and Scharnhorst at the bottom of the Arctic sea.

Battlecruiser Scharnhorst In Wilhelmshaven when first completed. The photo can be dated to early 1939 as indicated by the snowy conditions ashore. Note ship’s badge mounted on her bow. Although the Scharnhorst was the ”class” ship and was the first to be laid down and the first to be launched, her sister Gneisenau was completed quicker and was the first to enter service.

Commissioning ceremony of Scharnhorst on 7 January 1939.

Gneisenau’s final silhouette. The main criticism of her initial design was the relatively low deck height above the water, which made the ship ”wet” in North Atlantic conditions. This led to alterations in the sheer line and installation of the ’Atlantic Bow’ in a winter 1938 refit. She conducted trials in the Atlantic in June, 1939.

Scharnhorst with a similar (but not identical) ”Atlantic” bow installed in July-August 1939. Note the Arado Ar 196 seaplanes on the ship’s two catapults.

Scharnhorst with her crew her crew manning the rail along the modified bow.

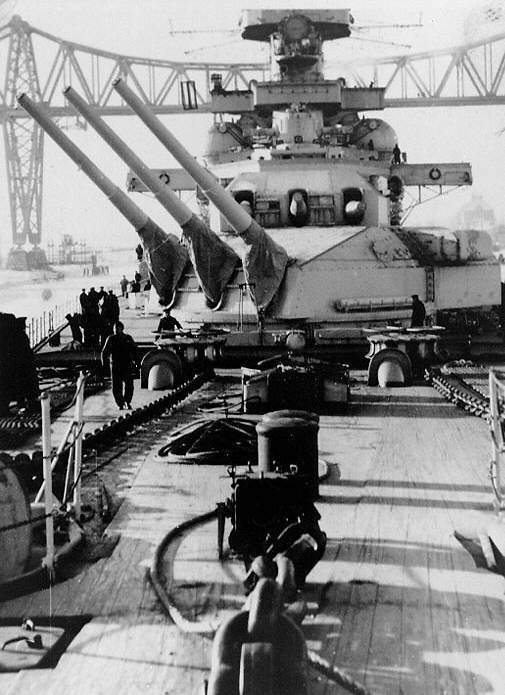

View of the Gneisenau’s forward two triple 283mm (11″) gun turrets, with forecastle and capstans in the foreground, circa later 1939 or 1940. The battleship Scharnhorst is in the left distance. She has been refitted with a ”clipper” bow.

Battlecruisers Scharnhorst (left) and Gneisenau in an unidentified German port, circa 1939-41.

A well-known propaganda photo of the initial war period, showing Günther Prien’s U-47 arriving at Kiel on 23 October 1939, returning from the mission in which she sank the British battleship Royal Oak inside Scapa Flow on 14 October. The battlecruiser Scharnhorst is in the background.

The port forward 150mm turret of the Gneisenau (or Scharnhorst) seen from ahead. Single-mounted 150mm guns are beyond, at main deck level, with 105mm twin anti-aircraft guns above.

The wooden foredeck of Scharnhorst, with anchor handling gear in the foreground and two triple 283mm gun turrets behind. The silhouette of the bridge in the background indicates that this photo was taken at Kiel during the winter of 1939-40.

The most famous naval battle involving German twin battlecruisers was the sinking the British aircraft carrier Glorious off Norway, 8 June 1940. This photograph shows Scharnhorst firing her forward 283mm guns during this very engagement. Photographed from the Gneisenau.

German warships in a Norwegian port, probably Trondheim, in June 1940. Battlecruiser Gneisenau is at left, with Scharnhorst in the left middle distance and heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper in right centre.

Photographed through a porthole on the battleship Scharnhorst, during the winter of 1939-40. Probably taken in late January 1940, when Scharnhorst arrived in the Baltic from Wilhelmshaven, joining Gneisenau to work up for combat operations.

View from the forward superstructure towards the bow, with the ice cover accumulating on the 283mm gun turrets. Although the installation of ”Atlantic bow” improved deck conditions in rough waters, in stormy seas the ship still took plenty of surf across the deck.

Operation ”Cerberus”, German heavy ships steaming up the English Channel, en route from Brest to Wilhelmshaven, 12 February 1942. Photographed from the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen, the Gneisenau is next ahead, with Scharnhorst visible in the distance. Although the Channel Dash was a huge propaganda victory for the Germans, both the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau hit mines and were put out of operations for months – indeed, the Gneisenau would never see battle again.

After operation ”Cerberus”, only the Scharnhorst was ever restored to active service, and moved to Norway together with Tirpitz to threaten Allied Lend-Lease convoys in the Arctic. Here she lies in in the Alta Fjord, 1943.

The standstill of service in northern Norway was agonizing for the crews, who were becoming more and more eager to go into action. Such feelings were also growing in German high command, but given the marginal strength of Kriegsmarine’s remaining force, giving in for these sentiments meant a disaster waiting to happen. In a single action on Christmas day 1943, Scharnhorst was ordered to sea in appalling weather to attack the convoy JW 55B, only to go straight into a trap orchestrated by the British. Scharnhorst, which early during the engagement lost its fire control radar, put up a heroic resistance against HMS Duke of York and a number of Royal Navy cruisers. She went to bottom leaving only 36 survivors of a total complement of 1,968 men.

. Later that evening Admiral Bruce Fraser briefed his officers on board Duke of York: ”I hope that if any of you are ever called upon to lead a ship into action against an opponent many times superior, you will command your ship as gallantly as Scharnhorst was commanded today”.

This article was originally published in IPMS stockholm Magazine in June 2006